You Need To Think In Versions For Your Software? A Good Place To Start Is Git.

Today it is often common to just deploy updates as they are ready to go. But if that's not possible you need to plan and manage versions thoroughly. Starting with this right in Git can make things really fast and easy.

Published on Thu, December 01, 2016

For many decades shipping a software meant to deliver it through physical media: floppy disks, compact discs, flash drives, you name it. This need to provide "a box" to get your software to your customers almost always implied fixed deadlines, so your bits and bytes made it to the factory in time.

And even if you are now able to deploy updates of your web app 50 times a day, because all the tools needed for that became ubiquitous industrial standards in the last decade or so, there are many, many vendors still carrying their mindest of managing versions of different iterations of their products.

Be it because of external constraints of their respected markets, or be it because of technical limitations. Shipping a fix for your broken last version of your app? That may only just work on Android, but on iOS not so much, because Apple needs at least some hours if not a couple of days to review your update.

And even if you could ship immediately, you may work in a field where your users would not acceppt even tiny bugs, because they depend heavily on your software. So quality asssurance is an issue here, which means you need to set up a process to make sure every release is being tested in depth.

So You Start To Think In Versions Of Your Software

What I usually see is some versions being worked on in parallel. Let's say 1.0.0 is the one which is currently out in the wild, and you are already working on the next set of features coming with 1.1.0. And there may even someone already be working on some experimental stuff which is on the roadmap for 1.2.0.

Now there happens to be this really nasty bug which nobody found before 1.0.0 was released and which needs to be fixed as soon as possible. Your work on 1.1.0 isn't done yet, so you can't wait to ship the fix with the next planned version.

That's the moment where you want to introduce a hotifx version 1.0.1. And you end up – for a short period of time – with 4 versions being developed in parallel:

- 1.0.0 // V1, already released

-- 1.0.1 // Hotfix, needs to be released before V2

- 1.1.0 // V2, regular release, in the works

- 1.2.0 // V3, regular release, in the works

Adapting Git Flow

Back in 2010 Vincent Driessen introcuded Git Flow, "a successful Git branching model", which, as far as I can tell, really made a great career. I am a huge fan of this approach and I am using it for a couple of years now in a variety of projects.

But having to deal with versioning in some larger projects led to some experiments and adaptions to the original concept, which proved to work really good not only in theory but practice:

- 1.0.0/master

-- 1.0.1/dev

-- 1.0.1/bug/this-nasty-thing-we-must-get-rid-of

-- 1.0.1/master

- 1.1.0/dev

- 1.1.0/feature/some-cool-stuff-a

- 1.1.0/feature/some-cool-stuff-b

- 1.1.0/feature/some-cool-stuff-c

- 1.1.0/master

- 1.2.0/dev

- 1.2.0/feature/experimental-stuff-d

- 1.2.0/master

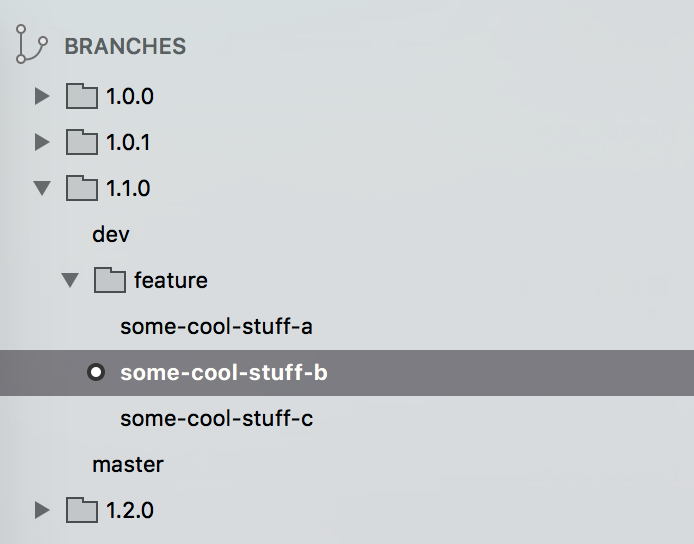

Looks chaotic? Then take a look at how SourceTree represents such a branch structure:

Looks tidy, doesn't it?

No Magic, Just Powerful Naming Conventions

The basic idea is to still leverage all the advantages of a Git-Flow like approach, but to nest everything below version numbers. That's it!

If you make this the foundation of your processes, you can create new versions (like the hotfix 1.0.1 which has to be delivered asap) in an instant. You can also easily switch between different versions while always knowing "where you are", which is tremendously valuable when working on a large codebase.

Of course that's not the end.

I did for example implement the extraction of the version numbers during the automated build process of a multi-platform mobile app, to put those extracted version numbers into Info.plist (iOS) and AndroidManifest.xml, so there is no need for maintaining them in some (checked-in) config files or even worse, environment variables or something like that.

That is where the power of this approeach really starts to unfold.

Drop me a line and let me know!