Who Cares About Functional Programming?

For a long time, most developers in the software industry have spurned functional programming as a niche product that can only be used in either academics or a few rather exotic problem domains.

Published on Mon, September 23, 2019

The origin of this perception may have been that functional programming languages often ”look” and work fundamentally different than more popular ones, e.g., from the C family. That is not entirely dismissable. The first functional programming language, LISP, has been introduced 60 years ago by John McCarthy. Based on the groundbreaking work of Alonzo Church on the Lambda calculus, McCarthy created a whole new category of programming languages. Those languages would become widespread and successful first and foremost in the scientific community in the decades to come.

A Perceived Trend?

However, since the early 2000s, functional programming has become more and more popular in the software industry as well. In fact, already more than 20 years ago Philip Wadler presented ”an angry half-dozen” examples of functional programming use cases in the real world. For example, Erlang, which is today seen as one of the fundamental building blocks of applications serving billions of users every day.

In addition, programming languages that call themselves ”functional-first,” such as Scala and F# have been introduced. And established ”object-oriented” programming languages such as Java and C# adopt functional ideas with accelerating speed.

Furthermore, it can regularly be observed that experienced developers with a background from the object-oriented world, who come into contact with functional programming, soon become almost enthusiastic. Like Dean Wampler wrote:

Once you learn the benefits of functional programming, you find that it improves all the code you write. When I learned functional programming a few years ago, it re-energized my enthusiasm for programming. I saw new, exciting ways to approach old problems. The rigor of functional programming complemented the design and testing benefits of test-driven development, giving me greater confidence in my work.

At the same time, many companies still struggle to apply functional concepts and methods in concrete software projects. Although it can be assumed that doing so could provide them a competitive edge, as the example of Jet.com shows. For tactical reasons, Jet decided to adopt functional programming with the explicit goal of becoming an attractive target for the most talented developers on the market (unfortunately, the article describing that tactic has been taken offline). The company was eventually sold to Walmart for $3.3 billion only 2.5 years after it had been founded.

So functional programming is an established and mature programming paradigm. A variety of programming languages support it. Many developers who try it quickly ”get hooked.” Also, from an economic point of view of a company, it is possible to build a conclusive argument for its introduction. But still, in practice, it does not always find application in all the fields it would presumably provide benefits over current mainstream approaches.

Why is that?

Industry Adoption – Some Numbers

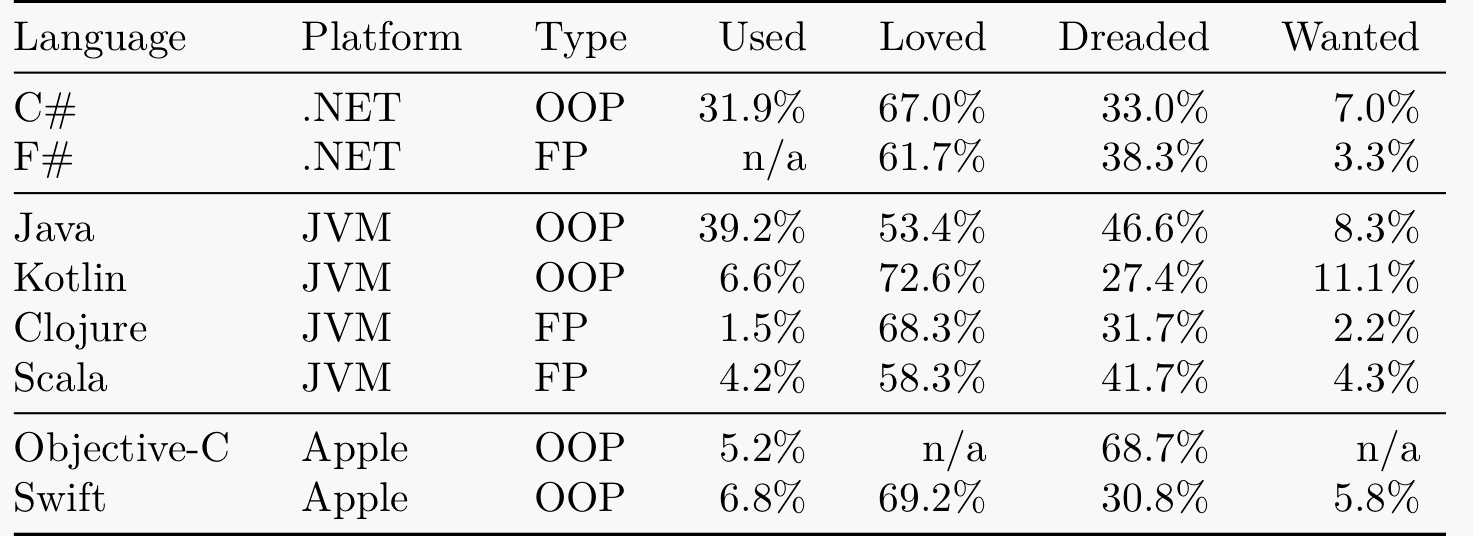

(Source: Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2019. Most of the languages listed here are in fact multi-paradigm languages which offer both functional and object-oriented capabilities. For the sake of argument, the type in this context refers to how those languages are mainly used and how they are marketed at the time of writing.)

If one thing gets clear from the numbers presented in this table, then that traditional and well-established languages like Java and C# still dominate their respective platforms. The exception here is Swift. Considering its young age (it was published in 2014), this seems surprising at first. However, looking at how discontent programmers are with Objective-C, not so much anymore. Not even the immaturity of the tooling around the language like its IDE Xcode could stop the migration.

The Chasm

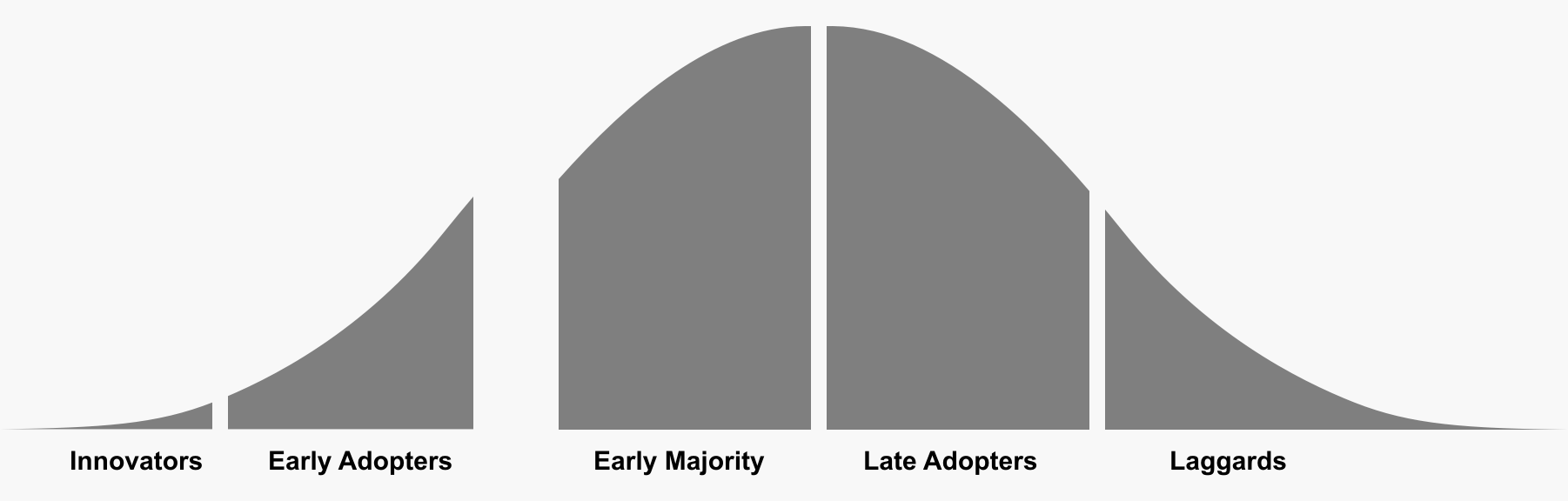

So why are most of the young contenders stuck with little recognition in their niches, while Swift is taking off so quickly? In 2015, Eric Sink predicted Swift’s success precisely while writing about why F# is not making ground against C#. He based his explanation on the theory of ”The Chasm” by Geoffrey A. Moore, first published 1991 in the book ”Crossing the Chasm”.

The chasm describes the gap of adoption between the group of early adopters and the majority of users. While early adopters may accept some problems on the way (like immature tooling), the majority expects a definite productivity improvement without disrupting the way they work (evolution instead of revolution). Eric Sink concludes that it needs severe problems to tackle and massive discontent with existing solutions in order to accept new approaches by the majority, which for those approaches then means ”to cross the chasm.”

For developers building applications in the Apple ecosystem, the primary hard problem seems to be Objective-C. In other words, ”the pain” is so significant that developers were almost desperately waiting for an alternative language and are now happily joining the movement of the Swift language.

How about the JVM and .NET? Java did evolve relatively slowly over the last years compared to C#, which early on got features like Generics, LINQ, and async/await. That may have made some room for improvement brought by new languages like Clojure and Scala, and especially Kotlin. Also, as seen in the table above, all three Java contenders are more appreciated than Java is itself within the JVM community.

Interestingly, the opposite seems to be the case for .NET: F# programmers love their language, but so do C# programmers. Which may explain the low adoption rate of F# compared to C#.

The Need For A Killer App

What could be done to make functional programming attractive for a broader audience? Philip Wadler lists several factors that a functional language must support in order to attract people to adopt it on a larger scale:

To be widely used, a language should support interlanguage working, possess extensive libraries, be highly portable, have a stable and easy to install implementation, come with debuggers and profilers, be accompanied by training courses, and have a good track record on previous projects.

The first five of those factors, which are mainly technical, are provided by almost all of the functional languages.

Training, as the sixth factor, is indeed a problem not to be underestimated. As Konrad Hinsen notes, ”functional programming is very different from traditional programming ... and thus requires a lot of learning and unlearning.” However, as some of the functional languages and architectures become more and more widespread, a lot of learning materials are being published, making it easier today to dig into the matter than ever before. Also, new teaching methods are tested which try to teach FP to developers used to other programming paradigms, especially OOP.

A good track record, the seventh factor, however, is probably the hardest part and the missing piece. Philip Wadler calls it the need for a ”killer app”:

Experience shows that users will be drawn to a language if it lets them conveniently do something that otherwise is difficult to achieve. Like other new technologies, functional languages must seek their killer app.

Signs Of Hope

Dean Wampler and Tony Clark make a case for FP to be the key to solve hard problems occurring in concurrent computing as with its concepts of immutability and functions free of side effects. That, for example, may have helped Scala to gain traction as Akka, ”a toolkit for building highly concurrent, distributed, and resilient message-driven applications” is written in it.

On an even larger scale, functional programming can benefit from the latest trends in cloud computing towards serverless archictectures. As Leitner et al. note:

Building Serverless and FaaS applications requires a different mental model that emphasizes ’plugging together’ small microservices. ... Adopting this differentmental model may be different, but experience with functional programming and the immutable infrastructure paradigm helps.

In the field of mobile app development, Kotlin is since 2017 officially supported by Google for its Android platform, which may have lead to a significant boost in recognition and eventually, acceptance. Kotlin may, as of today, primarily be used in a more traditional imperative way. However, it also supports functional programming, which could sooner or later become attractive for many Android developers. Especially since functional programming with Swift starts to spread on the competing Apple platform, e.g., through the new development tool SwiftUI.

Conclusion

Despite all the prophecies of doom, functional programming can be considered an elementary part of today’s IT landscape. However, notwithstanding many examples of successful application, in comparison to other paradigms and especially OOP, it is still not a mainstream paradigm.

Following the theory of "The Chasm", FP would need to solve a severe problem that could not be solved with existing approaches in order to make a breakthrough (finding its "killer app"). Some trends in cloud computing and mobile app development offer some signs of hope at this point.

Drop me a line and let me know!